Jun 15, 2022

Book Review: Internment in Britain in 1940

Dr. Harold Goldmeier is an award-winning

entrepreneur receiving the Governor's Award (Illinois) for family investment

programs in the workplace from the Commission on the Status of Women. He was a

Research and Teaching Fellow at Harvard, worked for four Governors, and

recently sold his business in Chicago. Harold is Managing Partner of an

investment firm, a business management consultant, public speaker on business,

social and public policy issues, and taught international university students

in Tel Aviv.

80 million refugees roam the world today. We view all of them through a

political lens, and the language used to label runaways reveals our biases and

defines their treatment.

There are 5 million (good) refugees from the Ukraine. (Bad) illegals flood

America’s southern border. British officers are deporting (bothersome)

displaced persons to Rwanda. 3 million (ignored) Venezuelans seek political

asylum in Columbia. (Pathetic) African Blacks and Middle East Muslims drown and

others enslaved trekking from Africa and Syria. (Dismissed) Afghanis on the run

are just dying.

My father was a German-Jewish (enemy alien) refugee. The Nazis freed him

from Buchenwald around 1940. His mother bought him a visa to Panama. Hitler

expected refugees to be a burden to destination countries. Dad traveled from

Fulda to Hamburg, boarding a boat sailing to Panama. The ship refueled and

resupplied in England. Dad jumped off.

The British interned him in a camp for enemy aliens, Jews and non-Jews,

Orthodox and secular, working men and intellectuals. Interns had to convince

Colonel May that they were not spies. From concentration camp to internment

camp like a summer fling. We visited a cousin who spent her teen years in a

concentration camp. My young son piped up, “I’m going to camp this summer.” We

busted out laughing until my cousin wished he did not go to the same one she

survived.

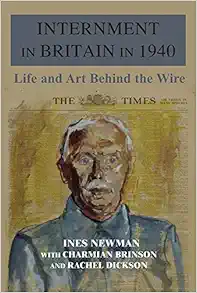

Now there is a book that tells the rest of the story. Internment in Britain

in 1940: Life and Art Behind the Wire by Ines Newman with Charmain Brinson

& Rachel Dickson (Vallentine Mitchell 2021) fills in the details about the

missing time. They built the book around a diary kept by Newman’s grandfather,

Wilhelm Hollitscher.

Holitscher’s story mirrors that of my father. Neither spoke much about life

in Buchenwald or the British internment camps until the Hollitscher diary was

found. Newman too “knew very little about our grandparents.”

The diary somehow found its way into London’s Weiner Library. It is a

first-hand, invaluable account for understanding how a nation at war protected

civilian refugees. I can hear my father’s voice and imagine life through

Hollitscher’s words and pictures; the days and nights in a refugee camp.

Newman and co-authors wrote Internment after years of extensive research.

The effort let Newman get to know her grandparents she missed growing up. The

book is 126 pages of relatively small font and single-spaced lines. There are

eleven pages of notes and a detailed index. Internment in Britain in 1940: Life

and Art Behind the Wire contributes importantly to the history of German Jews.

The book is in the best traditions of social anthropology. Meade and Benedict

might have praised it. The 20 illustrations about camp life and its colour

plates reproductions add valuable memories.

America closed its borders, refusing asylum to European Jews long before war

broke out. The British were at war and yet gave refuge to German Jews, Aryans,

and Italians. Foreign nationals, that is suspected enemy aliens, were under

arrest until cleared of being spies. They held 25,000 men and 4,000 women at

anyone time.

The interns were “called to appear in front of Aliens’ Tribunals throughout

Britain.” The Tribunals graded each person according to a perceived level of

security risk. Many avoided arrest and internment. America arrested and moved

120,000 citizens of Japanese ancestry, whether US citizens. My friend

Smitherton was one of them, but that is another story. The White Americans

running the war did not have relocation camps for Whites of German ancestry.

Hollitscher describes British camps as livable. Others were vermin-ridden

tents where “British soldiers—and even their officers—helped themselves in

plain sight to the inmates’ possessions.” Conditions were tough in the country.

Britain was at war. Supplies rationed. The country fell into a depression after

Russia collaborated with the Nazis, and the Polish and French militaries

collapsed.

The book offers significant background details, and the diary is

descriptive. Overall, its tone reflects my father’s attitude toward the

British. Some interned Jews believed conditions might be better if certain

guards, officers, and officials were not antisemitic, but it was better for

Jews in Britain than Japanese in the deserts and mountains of America.

The Hollitscher diary describes the daily privations, tedium, brooding and

“wrestling with their loss of identity.” But they were imaginative. When art

supplies were in short supply, camp artists burnt twigs “to create sticks of

charcoal; short beard hairs were plucked to use for brushes;” they made paints

from brick dust or vegetable juice ground with linseed oil or olive oil from

sardine cans.

In the diary’s Epilogue, there are ruminations by the Hollitscher whether

the war-time atmosphere resulted from government panic or the fault of the

“military machine” responsible for refugees. Newman believes “Fascism reaches

up into the highest circles…there exists an antisemitic alternative government,

supported by members of the governing classes, which has its own views and is

active and sabotages members of the government with a different view.”

This infection weaved its way through the Foreign Office and upper society.

It manifested in the British official collaboration with the Arab world. The

goal was to forefend a homeland for the Jews despite Prime Ministers

Churchill’s wartime and post-war position that “My heart is full of sympathy

for Zionism.” The book makes an important contribution to restructuring

attitudes and services to refugees and fills in gaps in modern Jewish history.

Reach thousands of readers with your ad by advertising on Life in Israel

No comments:

Post a Comment